For the National Labor Relations Board, 2012 could be déjà vu all over again.

For the National Labor Relations Board, 2012 could be déjà vu all over again.

Just last year the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in New Process Steel v. NLRB that the normally five-member board, which is responsible for enforcing federal labor laws, acted without authority when it handed down nearly 600 decisions with only two active members.

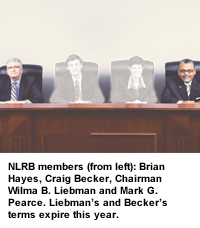

Until recently the NLRB had four members, but the term of one just expired and another will follow soon: board Chairman Wilma Liebman’s was at the end of August, and member Craig Becker’s is up in mid-December. And if members of the Senate, angered over recent NLRB actions, block President Barack Obama’s attempts to fill those vacancies, the board could again drop to two members, rendering it unable to issue decisions.

Michael F. Kraemer of Hinckley, Allen & Snyder in Providence said the Supreme Court’s holding was a clear and definitive statement that two-member boards are impermissible.

“I really thought this was an open and shut question at this point,” he said. “I don’t think New Process Steel really leaves any room for interpretation.”

Indeed, Greenberg Traurig’s Joseph W. Ambash, who was part of the team that successfully represented New Process Steel, said the absence of a quorum, as required by the National Labor Relations Act, means the NLRB loses its authority.

“New Process Steel stands for the proposition that if the board falls below three members for any reason, it will be unable to render any kind of adjudicatory decision,” the Boston lawyer said. “Given the current political climate and the inability of Congress to agree on many issues, I am not surprised to hear that this could be an issue again.”

Pure politics

Recent NLRB actions have drawn vocal criticism from Republican lawmakers, making very real the possibility of a block on nominees for the upcoming vacancies.

In addition to delaying or blocking a confirmation vote on nominees, Senate Republicans could use a parliamentary procedure to prevent Obama from filling the vacancies through recess appointments.

Earlier this year, GOP senators prevented the Senate from breaking for the Memorial Day holiday by refusing to adjourn by unanimous consent, leaving the Senate in pro-forma session. That move barred Obama from making appointments without Senate consent. And given the recent political rancor over actions by the NLRB, an attempt to block Obama’s nominees — and strip the agency of much of its power — is more than a remote possibility.

John N. Raudabaugh, who served on the NLRB from 1990 to 1993, said the possibility of again operating with only two members undermines the respect people have for the board and its governing statute.

Raudabaugh, a lawyer at Nixon Peabody in Washington D.C., said shutting down final NLRB decision-making would be purely political.

“Try as they might, there is no getting around the fact that the board has to have a minimum of three members,” he said. “What was going on in New Process Steel was a legitimate effort to keep decision-making coming, but it ultimately was not a permissible way to handle the situation.”

House time

The controversy flared after the NLRB’s general counsel brought what could be the largest labor lawsuit this century against Boeing Co., alleging its decision to shift operations from a union plant to a non-union shop in another state constituted an unfair labor practice.

The Republican-controlled House Committee on Oversight and Government Relations responded by calling a hearing in June titled “Unionization Through Regulation: The NLRB’s Holding Pattern on Free Enterprise.”

The committee’s chairman, Rep. Darrell E. Issa, R-Calif., called the NLRB’s lawsuit “an unacceptable course of action” that “exceeded their statutory authority to pursue a politically driven agenda.”

But in his testimony at the hearing, NLRB general counsel Lafe Solomon defended the Boeing suit, saying that “in the absence of a mutually acceptable settlement … both Boeing and the Machinists Union have a legal right to present their evidence and arguments in a trial and to have those issues be decided by the board and federal courts.”

Soon after, the agency announced a proposed rule to speed up the timeframe for unionization elections and postpone litigation over voter eligibility until after the election, drawing more ire from congressional Republicans and business groups such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which is considering seeking an injunction against the agency should the rule be finalized.

Unpredictable

Given those controversies, practitioners say they are preparing for Senate Republicans to push back on NLRB nominees.

“I think that Republicans and certainly the far right would like nothing better than to shut the NLRB down by blocking any attempt at filling those vacancies,” said William E. Hannum III, a partner at the management-side labor and employment firm Schwartz Hannum in Andover, Mass.

In the meantime, the situation has created a headache for labor attorneys.

“The problem from the standpoint of practicing law is that we need to make judgment calls on a regular basis,” said Victor T. Geraci, an employer-side lawyer from McDonald Hopkins in Ohio. “We have to make those judgments for our clients, who are paying for that advice. The ability to predict future action in circumstances where you don’t even know the number of board members there will be makes the job that much more difficult.”

Kraemer, a partner in Hinckley, Allen & Snyder’s labor and employment group, said even if the NLRB’s membership falls below a quorum, most litigation will continue. Agency hearing officers and regional directors at NLRB regional offices will still adjudicate disputes.

“The actual day-to-day work of the board is done by the various regional offices, and the overwhelming majority of cases never get to the board itself,” Kraemer said. “I’ve been doing this for a long time, and the percentage of cases that actually go to the board for a decision is probably in the 2 percent range.”

But appeals of those rulings will sit in limbo until the NLRB has the authority to rule on them, causing a bottleneck effect that can make the already lengthy labor litigation process even longer.

“The impact [on labor lawyers] really is the uncertainty that it brings to the process,” said Laurence M. Goodman, a partner in the Philadelphia office of Willig, Williams & Davidson. “From a union point of view, it gives employers the ability to delay what is already a long, drawn-out process in many situations.”

Lawyers say there is still an open question as to whether the general counsel will be able to pursue injunctive relief.

Currently, the general counsel must seek authorization from the board to pursue injunctions. When the NLRB previously fell to two members, that authority was delegated to the general counsel, a move that was condoned by five circuit courts, but the Supreme Court has yet to consider that question.

Hannum said it is unclear who would be hurt more by a potential NLRB shutdown: unions or management.

“I think the unions are probably going to come out ahead” in the event the board loses its quorum, he said. “[The agency] is leaning in unions’ favor at the moment. … To the extent that board agents can influence a case, they will be judge and jury until the board resumes functioning. So if you file a case with a board agent or regional director, who is coming down on the union side more often than not, you are going to be stuck with that decision for a while.”

But the union will not always win, Hannum said, because in “a lot of cases, the employer might be happy to sit around and wait to see if the board makes them post a notice.”

New England Biz Law Update

New England Biz Law Update