A recent U.S. Supreme Court decision allowing plaintiffs to use statistical evidence to establish class liability in a wage-and-hour case opens up a new battlefront in employment and other types of class action cases.

A recent U.S. Supreme Court decision allowing plaintiffs to use statistical evidence to establish class liability in a wage-and-hour case opens up a new battlefront in employment and other types of class action cases.

The case involved current and former workers at a Tyson Foods pork processing plant in Iowa. The plaintiffs sued because Tyson paid some but not all workers for “donning and doffing” — the time employees spend putting on and removing protective gear for their work. They sought certification of their Fair Labor Standards Act claims as a collective action and class certification of their Iowa wage claim.

Tyson, which did not keep records of the time the employees spent donning and doffing, said the workers’ claims were not similar enough for class certification.

The plaintiffs relied on a study conducted by an industrial relations expert that estimated the time workers in three different departments of Tyson typically spend on such activities.

In a 6-2 ruling late last month, the Supreme Court held that the federal District Court did not erroneously certify the class in Tyson Foods Inc. v. Bouaphakeo, et al., declining the invitation of Tyson and business groups to adopt a broad rule against the use of statistical or “representative” evidence in class action cases. The decision leaves intact the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals’ affirmance of the jury’s award of approximately $2.9 million to the workers.

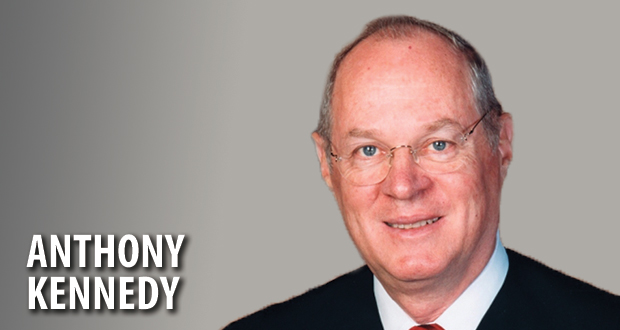

Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy distinguished Tyson from the court’s 2011 holding in Wal-Mart Stores Inc. v. Dukes, a gender discrimination case in which the court reversed class certification on the ground that the plaintiffs did not share common questions of fact or law. Unlike the Wal-Mart employees, Kennedy wrote, the Tyson employees could have introduced their expert’s study in individual suits because they worked in the same facility, performed similar tasks, and were paid under the same policy.

Instead of announcing general rules for the use of statistical evidence in all class action cases, Kennedy wrote that whether and when statistical evidence can be used to establish classwide liability will depend on the “purpose for which the evidence is being introduced and on ‘the elements of the underlying cause of action.’”

The court concluded the statistical evidence presented by the Tyson employees’ expert was a permissible means of establishing hours worked in their class action because each class member could have relied on that sample to establish liability had each brought an individual action.

“Rather than absolving the employees from proving individual injury, the representative evidence here was a permissible means of making that very showing,” Kennedy wrote.

Removing a hurdle

Louise A. Herman, an attorney in Providence, Rhode Island, who represents plaintiffs in wage-and-hour cases, said Tyson establishes that statistical sampling is appropriate when there are a number of employees subject to the same policy and where there is a pattern and practice occurring in the workplace.

“There are instances when statistical sampling and representative sampling is appropriate. No longer can employers assume that employees are going to have to prove their claims individually,” Herman said.

The ruling also is important in that the court found Tyson should not benefit from its failure to keep records, she said, adding that the decision will help her prove liability in cases in which her clients do not have access to the evidence they need.

“It would be incredibly difficult and costly and burdensome to have to prove each claim individually,” she noted.

Tyson removes “one of the major hurdles” to certifying employment class actions that plaintiffs have faced since Wal-Mart, said plaintiffs’ employment lawyer Philip Gordon of Boston.

“The judge only has to decide, ‘How reliable is the statistical evidence in terms of proving or disproving the elements?’” Gordon said.

The common-sense analysis in Tyson should put an end to some defense lawyers’ wildly broad interpretations of Wal-Mart, said Thomas M. Sobol, who represents plaintiffs in class action cases.

“The role of aggregate evidence — of representational evidence — is fundamental to class action practice, and this decision gives it the good housekeeping seal of approval,” Sobol said.

Sobol said he expects Tyson also to impact cases outside the wage-and-hour arena. In health care fraud cases involving pharmaceutical pricing, for example, there is often aggregate evidence of the impact of pricing fraud, he said.

“The rationale the court employs should have broad impact elsewhere,” said the attorney from Cambridge, Massachusetts.

But Boston’s Donald R. Frederico, who defends consumer and employment class actions, called the ruling “very limited” due to the fact that the Supreme Court did not adopt a broad categorical rule. Further, he said the court declined to reach the critical, related issue of how to deal with a class that includes uninjured class members.

Nevertheless, he said, “both plaintiffs and defendants will cite the decision in a variety of class action cases.”

Frederico also noted that Tyson did not challenge the admissibility of the plaintiffs’ statistical evidence under the teachings outlined in the Supreme Court’s 1993 Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc. ruling, which determined the standard for admitting expert testimony in federal courts.

“Defendants would be well advised in appropriate cases to make sure they mount their Daubert challenges at the same time as they oppose class certification when statistical evidence is offered,” Frederico said.

Time differences

Until 1998, Tyson compensated employees at its Storm Lake, Iowa, plant only for time spent at their workstations, or what it called “gang-time.”

Following a federal court injunction and U.S. Department of Labor suit, Tyson began paying employers for four minutes a day of so-called K-code time to don and doff protective gear.

In 2007, Tyson started paying some workers daily K-code time of four to eight minutes, while others went uncompensated for K-code time. The company never clocked the actual time workers spent donning and doffing the gear.

The plaintiffs claimed Tyson violated the FLSA by not paying them overtime hours, which they would have accrued had the company counted the time for donning and doffing — an activity that they argued was “indispensable to their hazardous work.”

The U.S. District Court certified a 3,344-member class.

During the jury trial, plaintiffs’ expert Dr. Kenneth Mericle testified that, based on 744 videotaped observations, he determined the average donning and doffing time to be 21.25 minutes a day for “kill department” employees, and 18 minutes a day for employees in the “cut” and “retrim” departments.

A second plaintiffs’ expert, Dr. Liesel Fox, determined which plaintiffs had overtime claims by adding Mericle’s averages to the hours on individual employees’ timesheets. According to Fox’s calculations, the aggregate unpaid wages totaled $6.7 million.

The jury found that the donning and doffing time was compensable, except for meal breaks, and awarded damages of about $2.9 million.

Representative evidence

Kennedy rejected Tyson’s argument that using a representative sample freed each plaintiff employee from the responsibility of proving personal injury and deprived the defendant of the ability to litigate its defenses.

“If the sample could have sustained a reasonable jury finding as to hours worked in each employee’s individual action, that sample is a permissible means of establishing the employees’ hours worked in a class action,” Kennedy wrote.

Like the 8th Circuit, Kennedy relied on the 1946 Supreme Court ruling in Anderson v. Mt. Clemens Pottery Co., which held that, when an employer fails to comply with the statutory burden of keeping proper records, the FLSA and public policy “militate against” making the employee’s burden of proof an impossible hurdle.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. submitted a concurrence stating his concern that the District Court on remand may not be able to craft a method for awarding damages only to class members who suffered an actual injury.

Roberts also agreed with the dissent that Anderson did not provide a “special relaxed rule” allowing plaintiffs to use otherwise inadequate evidence in FLSA cases, but he adopted the majority’s conclusion that the jury could find that the study met the standard of proof applicable in any case.

Roberts wrote that if there was no way to guarantee that only injured class members would receive damages, then the award could not stand.

In a dissent joined by Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that Tyson was prejudiced at trial because the District Court did not meet its obligation to subject the representative evidence to a rigorous analysis.

“By focusing on similarities irrelevant to whether employees spend variable times on the task for which they are allegedly undercompensated, the majority would allow representative evidence to establish classwide liability even where much of the class might not have overtime claims at all,” Thomas wrote.

New England Biz Law Update

New England Biz Law Update