A federal appellate court has struck down the National Labor Relations Board’s controversial notice posting rule, the latest in a series of blows to the agency that has been mired in legal controversy.

A federal appellate court has struck down the National Labor Relations Board’s controversial notice posting rule, the latest in a series of blows to the agency that has been mired in legal controversy.

Attorneys say the ruling in National Association of Manufacturers v. NLRB could lead to challenges of similar workplace posting rules from other agencies, including the Department of Labor, the Department of Justice and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

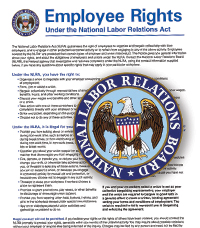

The NLRB rule required employers to place 11-by-17-inch posters in their workplaces notifying workers of their rights under the National Labor Relations Act to join together to improve wages and working conditions, to unionize, to bargain collectively with their employer, and to refrain from any of those activities.

The rule also made failure to post the notice an unfair labor practice under the law, and tolled the statute of limitations for employees to file a claim until the notice was posted.

After a D.C. District Court struck down a portion of the rule a month before its original effective date of April 30, 2012, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit temporarily blocked its implementation.

The D.C. Circuit invalidated the rule in its entirety on May 7, finding that it violated the First Amendment free speech principles codified in §8(c) of the NLRA.

“Of course we are not faced with a regulation forbidding employers from disseminating information someone else has created,” Judge A. Raymond Randolph wrote on behalf of the panel. “Instead, the Board’s rule requires employers to disseminate such information, upon pain of being held to have committed an unfair labor practice. But that difference hardly ends the matter. The right to disseminate another’s speech necessarily includes the right to decide not to disseminate it.”

Randolph noted that the rule applies to more than 6 million employers, most of them small businesses, and that it was a departure from the board’s historic practice of avoiding the use of rulemaking to impose new policies.

‘Coerced speech’

Peter Bennett, a labor relations and employment lawyer who has written about the case, said the National Association of Manufacturers ruling should curb the NLRB from engaging in aggressive rule- and policy-making activity.

Bennett, whose firm has offices in Boston and Maine, said the court’s decision is grounded in constitutional principles and is unlikely to be decided differently by other circuits.

“It’s a form of coerced speech because it essentially required employers to advertise to their employees that they have a right to form a union,” he said. “The First Amendment gives the employer the right to refrain from speech, but the NLRB was taking the position that a failure to post the rule could lead to punishment as an unfair labor practice. One of the significant outcomes from this decision is that the court clearly said they cannot do that.”

In recent years, Bennett said, the NLRB had been “working behind the scenes” to take actions designed to hurt employers.

“The fact that [the D.C. Circuit ruling] just happens to be published and [is] in everyone’s face may encourage practitioners who have issues with the NLRB to push harder to take them to the court of appeals,” he said.

Michael F. Kraemer of White & Williams in Boston said the NLRB is a highly political body, which either acts in favor of employees or management depending on which party controls the White House.

He said the NLRB’s posting rule created anxiety among employers, particularly human resources professionals, because the NLRB — unlike OSHA, the DOL and the EEOC — traditionally does not formulate rules.

“The NLRB usually interprets the statute by the cases it decides. It has not historically been a rule-making board. And that’s one of the reasons why this was so surprising,” Kraemer said.

Unions have been “decimated” over the past few decades, he said, noting that the notice rule was “one of many things” the NLRB had done under President Obama to try to make life easier for employees.

Kraemer said he considered the rule itself “moronic” and unlikely to help unions given the many notices employers are required to post on bulletin boards regarding workers’ compensation and other matters. Only an employee intent on reading every item posted would likely “take anything away,” he said.

Opening the door

A U.S. District Court judge in South Carolina also struck down the rule, holding in 2012 that the board exceeded its statutory authority in imposing it. The appeal in that case, Chamber of Commerce v. NLRB, is pending before the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Jeffrey M. Hirsch, a professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law in Chapel Hill, said the D.C. Circuit’s First Amendment analysis might open the door to challenges to notices employers are required to post under the Fair Labor Standards Act, the Occupational Safety and Health Act and other laws.

“The opinion is largely [a] First Amendment interpretation,” said Hirsch, a former appellate attorney for the NLRB. “They are basally finding a notice posting rule, with [a penalty imposed] for refusing to post it, compelled speech that is unconstitutional.”

But, Hirsch said, the reliance on free speech in §8(c) of the law may prove a crucial distinction from other statutes.

Howard K. Kurman, a management-side lawyer in Maryland, said he does not expect to see challenges beyond the NLRB context — not only because of the NLRA’s language, but also because of the uniquely pro-union stance the NLRB’s poster is seen to embody.

“This case would have never come to light had this poster not been composed as overly pro-union,” he said.

Kurman added that the ruling was not surprising, given the increasing number of federal courts that have pushed back on NLRB policies that are seen as overbroad or beyond the agency’s authority.

“There has been and continues to be this push and pull between the Obama administration’s NLRB and the courts,” Kurman said.

The D.C. Circuit opinion mentioned its ruling from earlier this year striking down Obama’s three recess appointments to the board as unconstitutional. The Obama administration has asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review that decision, which has called into question the authority of the board to issue hundreds of decisions and rulemaking actions over the last 18 months.

However, Randolph’s decision found that because the rule was promulgated when the board had a quorum of Senate-confirmed members, the subsequent recess appointments did not affect that case, even though the rule was set to go into effect after the appointments were made.

New England Biz Law Update

New England Biz Law Update