A provision in the Sarbanes-Oxley Act protecting whistleblowers from retaliation does not extend to employees of private companies that act under contract as advisers to, and managers of, mutual funds, the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has decided in a split decision.

A provision in the Sarbanes-Oxley Act protecting whistleblowers from retaliation does not extend to employees of private companies that act under contract as advisers to, and managers of, mutual funds, the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has decided in a split decision.

The defendant employers argued that the provision applies only to employees of publicly traded companies.

A 1st Circuit majority agreed.

“Although there is a close relationship between the private investment adviser defendants and their client mutual funds, as pointed out by the plaintiffs and the SEC as amicus curiae, the two entities are separate because Congress wanted it that way,” Chief Judge Sandra L. Lynch wrote for the court. “Had Congress intended to ignore that separation and cover the employees of private investment advisers for whistleblower protections, it would have done so explicitly in [18 U.S.C.] §1514A(a). However, it did not.”

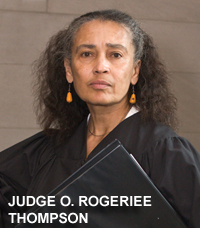

Judge O. Rogeriee Thompson dissented.

“[M]y colleagues impose an unwarranted restriction on the intentionally broad language of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, employ a method of statutory construction diametrically opposed to the analysis this same panel employed just weeks ago, take pains to avoid paying any heed to considered agency views to which circuit precedent compels deference, and as a result bar a significant class of potential securities-fraud whistleblowers from any legal protection,” she asserted.

The 73-page decision is Lawson, et al. v. FMR LLC, et al.

Paul E. Nemser of Boston argued the appeal on behalf of the defendant employers. He was opposed by Indira Talwani, also of Boston.

Whistleblowing alleged

Both plaintiffs, Jackie Hosang Lawson and Jonathan M. Zang, sued their former employers — private companies that provide advising or management services by contract to the Fidelity family of mutual funds.

Zang alleged that he had been terminated in retaliation for raising concerns about inaccuracies in a draft-revised registration statement for certain Fidelity funds. He contended that he reasonably believed the inaccuracies violated several federal securities laws.

Lawson alleged retaliation against her after she raised concerns primarily relating to cost accounting methodologies. She resigned in September 2007, claiming that she had been constructively discharged.

U.S. District Court Judge Douglas P. Woodlock denied a defense motion to dismiss the two complaints. The judge concluded that the whistleblower protection provision within §806 of SOX extends its coverage beyond “employees” of “public” companies to encompass also the employees of private companies that are contractors or subcontractors to those public companies.

Concerned that that interpretation could be considered too broad, Woodlock then imposed a limitation that the employees must be reporting violations “relating to fraud against shareholders.”

Textual focus

“The question is whether Congress intended the whistleblower provisions of §1514A also to apply to those who are employees of a contractor or subcontractor to a public company and who engage in protected activity,” Lynch said. “No court of appeals has ruled on this issue.”

The plaintiffs argued that the covered “employee” who is given whistleblower protection includes both the employees of public companies and those who are the employees of the public companies’ officers, employees, contractors, subcontractors or agents.

“The title of section 806 and the caption of §1514A(a) are statements of congressional intent which go against plaintiffs’ interpretation,” Lynch responded. “Other provisions of SOX also support and are more consistent with the defendants’ reading and inconsistent with the plaintiffs’ reading.”

The majority’s reading of “employee” as excluding from coverage employees of officers, employees, contractors, subcontractors and agents of public companies “is also strongly confirmed by the pre-passage legislative history of this section and other sections of SOX and the purpose of the legislation,” Lynch said. “Further confirmation is provided by the later actions of Congress in rejecting a bill meant to amend SOX and in congressional acceptance of other amendments.”

The majority reasoned that the broader reading of the statute offered by the plaintiffs “would provide an impermissible end run around Congress’s choice to limit whistleblower protection in that subsection to the employees of two categories of companies the title and caption call ‘publicly traded companies.’”

A dissenting view

Thompson said the majority judges “ignore the text of §806, take a myopic view of the section’s context, wrongly inflate the section’s title into operative law, and attribute a limiting intent to legislative history that in reality supports a broad reading of the statute.”

By rejecting Congress’ intentional breadth, she said, “the majority undermine the legislative process in precisely the same way that the Supreme Court has warned against time and time again in the context of implied rights of action. That they do so by restricting a broad statute rather than expanding a narrow statute is beside the point: they are still usurping Congress’s lawmaking role in our system of government.”

The dissenting judge pointed out that the plaintiffs’ position was supported by the U.S. Department of Labor as well as the Securities and Exchange Commission.

“Not only does Sarbanes-Oxley §806 by its terms protect employees of contractors of public companies, but the agency that handles every §806 whistleblower complaint has issued formal regulations recognizing that straightforward interpretation, and this court has held that the regulations are owed deference,” she said. “But, somehow, the authority of all three branches of government does not win the day: the majority disregard Congress’s broad language, reject the agency’s regulations out of hand, and do their best to neutralize this court’s [2009] decision in Day [v. Staples, Inc.], by labeling it both distinguishable and dicta.”

Thompson concluded that “§806 plainly protects whistleblower employees of contractors of public companies; digging deeper into the section’s context and legislative history only confirms the breadth of §806’s protections; considered agency views further support a broad read of the statute; and the majority have had to work very hard to reject not only our own precedent but also the views of the other branches of government, to say nothing of grammar and logic.”

New England Biz Law Update

New England Biz Law Update