An employer that repeatedly reprimanded an employee after she complained of racial discrimination could not be held liable for retaliation, the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has determined.

An employer that repeatedly reprimanded an employee after she complained of racial discrimination could not be held liable for retaliation, the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has determined.

The plaintiff employee argued that the written warnings she received amounted to an adverse employment action and created a hostile work environment.

But the 1st Circuit disagreed.

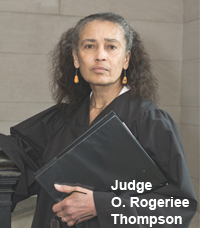

“[N]one of the reprimands here can be said to be material because none carried with it any tangible consequences,” Judge O. Rogeriee Thompson wrote for the unanimous court. “The [employer]’s conduct toward [the employee] was far from severe, never physically threatening, generally conducted in private so as not to be humiliating, and never overtly offensive.”

The 18-page decision is Bhatti v. Trustees of Boston University.

Sizing up the claim

Lawrence S. Elswit, an associate general counsel at Boston University, said the plaintiff’s case simply did not support the argument that she was the target of racial discrimination. Despite the employee’s claim of disparate treatment, the employer treated every worker the same, he said.

“They were all held to the same attendance standards, given the same amount of time off and all allowed to leave work a little early,” he said. “In addition, even as [the plaintiff’s] personal relationship with her supervisors deteriorated, she was simultaneously receiving good performance reviews, a very significant raise and other benefits related to her job.”

Elswit said the plaintiff’s case failed because she could not identify any concrete harm. Although the evidence showed that she suffered some distress at work, the medical evidence also demonstrated that the distress did not last long and was not particularly serious, he said.

Richard A. Mulhearn of Worcester, Mass., who represented the employee, acknowledged that his client was not fired and that she did not claim that she was passed over for a promotion because of the alleged discrimination. However, he said, there were issues of fact that, if presented to a jury, would have supported liability for discrimination and retaliation.

“Her damages lie in that she needed counseling. There was a substantial amount of time taken off from work as a result of the … stress that she was experiencing,” Mulhearn said. “It was affecting her big-time emotionally, and I don’t see how the court could find that the serial reprimands she was getting didn’t create a hostile work environment.”

Mulhearn said his client still works for the university and that the supervisor involved in the alleged discrimination was eventually terminated for cause.

“The federal court is not overly friendly to these cases. They find ways to basically dispose of them by summary judgment,” he said. “It’s puzzling that, one way or another, the court seems to always find a way to do it either by saying that you didn’t have enough evidence, or even if you did, it’s not a serious enough claim.”

‘Less-than-stellar management’

Plaintiff Claudine Bhatti began working as a dental hygienist at defendant Boston University’s Dental Health Center in 2003.

The defendant’s alleged discrimination against the plaintiff began at the outset of her employment in 2003, when supervisor Jacqueline Needham told her she had to perform 30 minutes of unpaid setup time every morning in addition to her 40-hour work week. In contrast, the plaintiff claimed, the three white hygienists in the office were credited for their setup time as a part of their 40-hour weeks.

The plaintiff also claimed that a so-called unwritten rule allowed her white counterparts to take extended lunch breaks and leave up to 15 minutes early without having to submit a written request and without being charged sick or vacation time. But if the plaintiff wanted a similar deviation from her scheduled workday — an extended lunch or early departure — she had to file a written request, and Needham would deduct the time from the plaintiff’s bank of sick or vacation time.

In 2005, the plaintiff confronted Needham about the perceived disparities. Dr. Eyad Haidar, who was director of the center, was drawn into the dispute.

After the plaintiff’s confrontation with Needham and her follow-up with Haidar, the plaintiff said, management began retaliating against her. Specifically, she received written reprimands for infractions that were minor or did not occur at all, she said.

The plaintiff eventually filed suit in 2008 alleging discrimination, retaliation and a hostile work environment in violation of various federal laws.

The defendant answered and, in April 2010, filed a motion for summary judgment denying any discrimination, “but acknowledging that Bhatti had worked under less-than-stellar management.”

Massachusetts U.S. District Court Judge Richard G. Stearns granted the motion, holding that none of the plaintiff’s grievances, individually or in the aggregate, rose to the level of an adverse employment action necessary for her to succeed in her suit.

The judge further held that the defendant had presented evidence establishing that its management practices applied across the board to employees of all races and that the plaintiff failed to respond with adequate evidence of actual animus.

Interpersonal grievances

On appeal, the 1st Circuit found the plaintiff’s evidence insufficient to prove racial discrimination.

“The record reveals no scheduling disparity,” Thompson said. “[B]ecause there is no evidence in the record that Bhatti was ever actually denied a 10- to 15-minute early departure, such a nonexistent denial cannot support her discrimination claim.”

With regard to retaliation, Thompson said, the court had found in the past that a reprimand may constitute an adverse action, as in Billings v. Town of Grafton in 2008.

“[B]ut the reprimands at issue here are tamer beasts than the one in Billings,” Thompson said. “[E]ach was merely directed at correcting some workplace behavior that management perceived as needing correction; her working conditions were never altered except in the positive direction.”

The judge said the plaintiff “may well be right that these reprimands were undeserved — indeed, she presents enough evidence that we may safely presume her to be blameless (or nearly so) in each instance for summary judgment purposes — but a criticism that carries with it no consequences is not materially adverse and therefore not actionable.”

The 1st Circuit then addressed the plaintiff’s claim that the defendant subjected her to a racially-motivated hostile work environment in which she was reprimanded “for the slightest misstep and regularly belittled and mistreated by her supervisors.”

The court found it significant that the plaintiff pointed to no effect whatsoever on her work performance.

“True, she sought psychological counseling, but this is evidence of subjective offense at best,” Thompson said. “Objectively, the Center’s conduct here might have crossed the boundary from professional to unprofessional, but it never reached the level of abuse. And where a workplace objectively falls short of that ‘abusive’ high-water-mark, it cannot sustain a hostile-work-environment claim.”

In the end, the plaintiff succeeded only in showing “a litany of petty insults, vindictive behavior, and angry recriminations,” Thompson wrote. “As these are not actionable, we uphold the district court’s grant of summary judgment for the University on all claims.”

New England Biz Law Update

New England Biz Law Update